You aren't on the same internet as everyone else

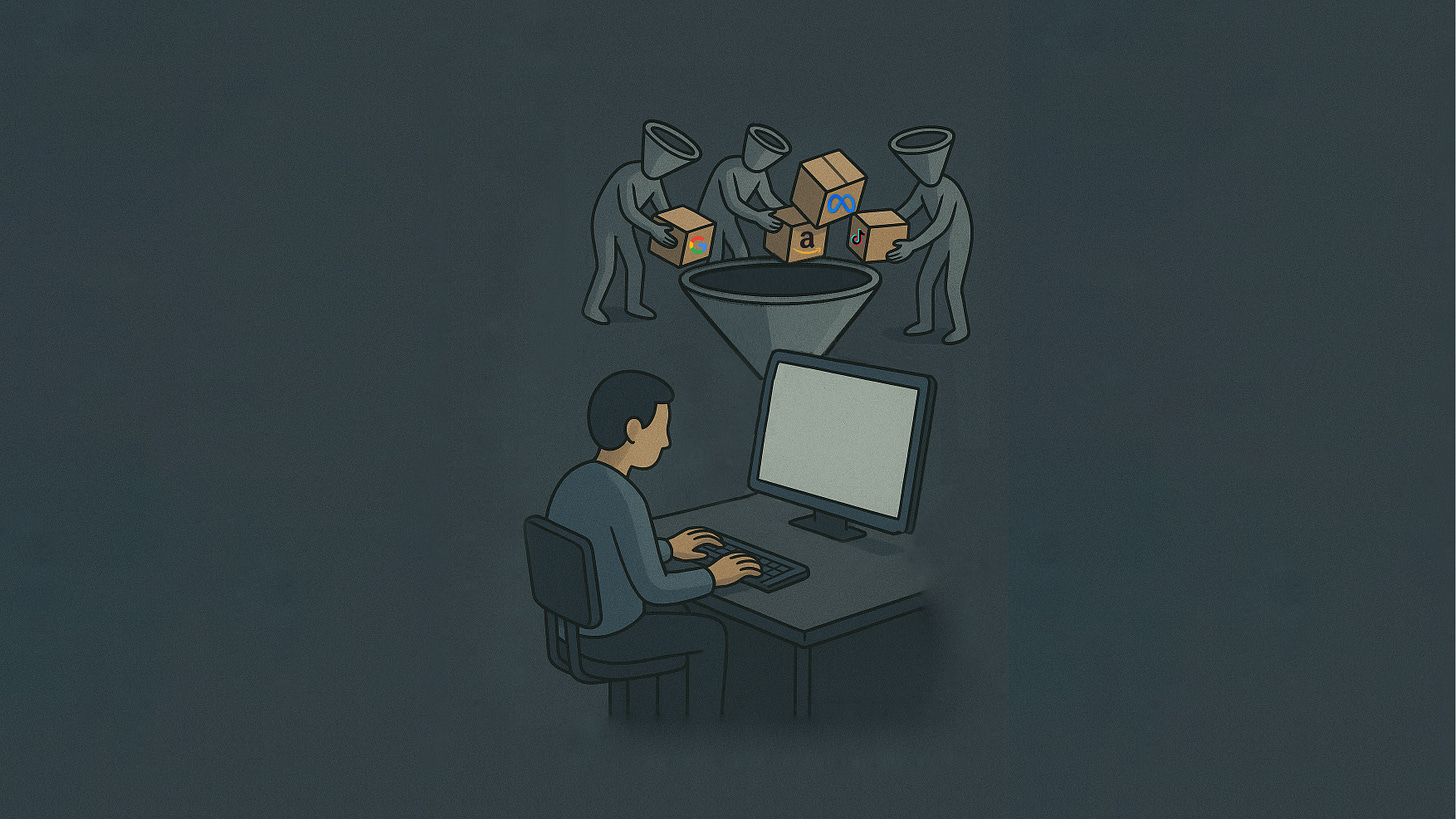

It's more of a pay-to-play funnel, than interconnected web.

As I did my morning doomscroll the other day waiting for the kettle to boil, I saw a combination of shocking footage of Israeli war crimes being committed in Palestine, restaurant reviews, some pop-culture news updates, a funny video or two of children and dogs tripping over and a few short clips from people ‘solving’ the mens mental health crisis, and discussions about the culturally ingrained homophobic attitudes of the AFL.

I also saw people demanding that others ‘speak up’ about at least 4 different ‘causes’ or ‘issues’.

‘How can people be silent’

‘Silence is complicity’

‘This is a national/international emergency’

While this was all only within a couple of minutes of scrolling, later in the day I opened the socials to see another post - shared by a Jewish friend of mine, which showed an interpretation, or ‘take’ that was completely different to mine. The abridged version of the post, from memory, cited the number of times Hamas had rejected a treaty, and was celebrating the impending invasion/action in Gaza, as it will strike the final blow and recover the hostages.

I know this person, and they are not a monster. They are not completely uncaring. They are not completely lacking in empathy - but the side of the conflict that they have been sharing, has been in stark contrast to the reams of footage and reporting that I’ve seen - particularly here on substack from Mosab Abu Toha and Owen Jones.

I often speak with people who come to completely different conclusions to me from what looks like the same circumstance or set of facts. People whose advocacy falls in direct opposition to mine, and whose interpretations seem so incredulous, that they border on disingenuous or wilfully ignorant.

Having had these conversations, one thing is painfully clear. They are not on the same internet as I am.

They are quite simply not seeing the same things I’m seeing, or reading the same things I’m reading. The commentary they are getting on the information that’s coming out is not the same as mine - and like me, they find solace in the community of people that agree with them.

This is not quite the way many of us think about the ‘Internet’. Considering the rapid pace of change, and the immense power of the vested commercial interests that control our access to the web, it’s not surprising. It’s also not reflective of what was intended by it’s creation. Tim Berners Lee1 -inventor of the World Wide Web had different ambitions for the internet -

“initially our feeling philosophically was that the web should be a neutral medium. It’s not for the web to try to correct humanity. The web would hopefully lead to humanity becoming more connected, and therefore, maybe more sympathetic to itself — and therefore, perhaps less conflict-ridden.”

The idea was that we would have the free flow of information, democratic, libertarian access to all the world’s insight and knowledge. People would be able to share things quickly and effectively, and of course - in the presence of all this access, better decisions would be made, and humanity would advance, together.

It’s clear that we are hardly less conflict-ridden and that the world wide web, and our experience of it, has been captured by corporate interests. The internet of the 2020’s is gatekept, curated and operated by a handful of enormous, wealthy, dominating tech companies that operate a pay-to-play fiefdom throttling our access to the web, and ensuring that we see (mostly) what they want us to see.

Amazon, Google, Meta, Apple, Microsoft - control the majority of our access to the internet. Through search, servers, software and social media applications they make decisions about what we see when we passively engage with the internet and when we actively use it. These companies don’t just serve us information when we aren’t paying attention, they decide what we see, even when we intentionally look for information.

We are more likely to stay online, to stay active and to feel better about our online experience when we see things that we agree with, and that we like.

We are also likely to stay online and stay active when we see things with which we vehemently disagree. Conflict creates clicks.

As a result, we see an internet that shows us things we really agree with and like (cue the memes about crazy family members, millennial stress and football) and things we really don’t agree with. “The content most likely to elicit impassioned responses is on the very subjects that people feel affect them personally.”2

Many people will then end up digging their heels in, and feeling more and more animosity towards ‘the other’, while drawing closer to the people who are cheering on their position.

“This may be attributed to a principle in psychology known as the “backfire effect” — that is, people often become counterintuitively more entrenched in their position when presented with data that conflicts with their beliefs.”3

The end result is a completely different, personalised internet experience for everyone. There is no ‘Inter-Net’ as we might think of it, we are simply being funnelled information specific to us, at specific times of the day, in specific ways - designed to keep us malleable and ready to make money for tech companies.

The main point that I’m trying to make, is that when we want to change minds and bring people together, we cannot take the information that we have for granted. Everyone is not seeing the same stuff.

If you want to work with people who disagree with you, in order to bring them round - you need to know what they are seeing and hearing. You need to understand what interpretation of events makes sense to them - what anxieties are being preyed upon, and what communities do they feel a part of.

A lot of the internet is people screaming into a void of people who either agree with them (their community) or those who vehemently disagree and want to argue or comment in bad faith (their opposition).

We need to pursue good faith conversations that work to get to the bottom of disagreements and fundamental misunderstandings.

We need to demonstrate reflection, consistency and patience as much as we’d like to see it reciprocated.

We need to decide if we are trying to make change, or simply shout into the void.

Dialogue or monologue.

It’s a lot harder to maintain the good faith dialogue required to understand others better and actually move people towards a better future for all - but it’s as important now as its ever been. Sometimes people are demonstrably wrong, and operating from false information and faulty premesis. The ‘demonstration’ that is required to illustrate those shortcomings to people however, vary greatly from person to person. Very few people respond well to simply being told ‘you’re wrong’ (even when they are). Being someone who will be listened to by people who disagree, is a real challenge in an age where we can avoid those challenges to our personal identities and understanding. It is, nonetheless, one of the most valuable kinds of online personalities in an age of polarising outrage and personal information curation.

My personal recommendation is to take as many of these conversations offline as you can, and to make the very difficult effort to see and understand what kind of things people you disagree with are ingesting - not so that you can counter it with your ‘correct’ facts and interpretations, but so that you can genuinely understand where they are coming from. Understanding someone’s anxieties and affiliations will go a long way to helping you work with them towards a common outcome.

Changing minds requires much more than I’m addressing here, but a great place to start when frustrations are building - is to remember that you aren’t on the same internet as everyone else. Act accordingly.

https://time.com/5549635/tim-berners-lee-interview-web/

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-psychology-of-internet-rage-2018051713852

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/the-psychology-of-internet-rage-2018051713852